Early in the new year of 1996 there was an unexpected visitor to Princess Diana’s apartment at Kensington Palace. He had arrived unseen, emerging from the boot of the Princess’s butler’s car.

Even though the furore over Panorama had subsided, Martin Bashir was taking no risks. Neither, more importantly, was Princess Diana.

The cloak-and-dagger element that had surrounded every aspect of their collaboration on the sensational interview six weeks earlier, in which the Princess had spoken openly on every aspect of her life within the Royal Family, had not let up.

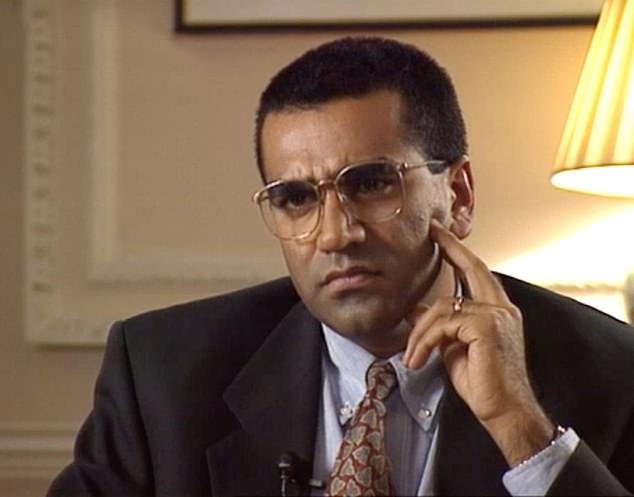

Martin Bashir, pictured, used devious methods to secure the controversial interview with Princess Diana

The aftermath had left Diana both elated and miserable. Elated because public support, which had initially wavered, had now strengthened, but miserable because she was increasingly uneasy about her future.

The practical cost of conspiring to make the programme had seen her position within the protective royal sphere considerably diminished with the order from the Queen for her and Prince Charles finally to divorce.

She had also been shattered by the loss of key senior staff. Press secretary Geoff Crawford had quit in November and now her private secretary, Patrick Jephson, had offered his resignation.

In her isolation it was inevitable, perhaps, that she turned to Bashir. The man whose soft, soothing manner had coaxed so many secrets from her lips became not just a figure of support but a confidant who helped shape her life as her marriage entered its final months.

But Bashir was unlike the smooth, well-groomed courtiers she had lost. Despite the ease with which he had reeled the Princess into his clutches, he was secretive and instinctively an outsider.

In the weeks since the programme aired on November 20, 1995, he had visited the palace only once — to pick up a Christmas card from the Princess. Now he was back again.

He would park his car in De Vere Gardens, a few streets away from the palace, and await the Princess’s butler, Paul Burrell.

Then he would hide under a back-seat blanket or, as he often did, clamber into the boot of Burrell’s car.

During the interview, which was broadcast on the BBC, Princess Diana admitted there had been three people in her marriage to Prince Charles

The reason was clear: he would not have to give his name or show his face to the police who guard the palace. With no record of his arrival, it meant that to all intents and purposes he was not there.

To be fair, he was not the only man smuggled in to see Diana in this way. Friends and lovers were sometimes slipped in using the same ruse.

Bashir, of course, was neither. But he was a controversial figure, even then.

Many of the Princess’s circle believed he had duped or tricked her into giving her interview in the first place. Within the BBC, questions were beginning to be asked about his methods and there were rumours of inquiries into how he had pulled it off.

For her part, Diana told me simply that: ‘He was the right person coming along with the right questions.’

There is no doubt an element of truth in what she said. She told another friend that she had felt sorry for the BBC reporter and ‘wanted to give him a leg up’ with his career.

Well, she certainly did that.

And what remains extraordinary is how a man she only met for the first time on September 19, 1995, was being warmly welcomed into Apartment 8 & 9 at Kensington Palace just seven weeks later with a camera crew and a barrage of questions that were to shatter the monarchy.

But what is less well-known is how, in the aftermath of his scoop, Bashir inserted himself into Diana’s life so successfully that she began to wonder if her trust in him was deeply misplaced.

She told me over lunch at the palace a year later on January 21, 1997, that she was frightened he would not keep the many secrets she had shared with him.

Earl Spencer, pictured, believes the interview and the way it had been secured contributed to his sister’s death

Uppermost in her mind, she said, was private correspondence she had allowed him to take away and read. This included, she told me, not just notes between her and Prince Charles but also a cache of letters she had exchanged with Prince Philip after the separation.

They were highly confidential and personal. And now doubts were crowding into her mind about the man, two years her junior, who not long before she had declared ‘has given me my wings’.

Given that she was so cautious in her friendships, the way in which Martin Bashir became such an indispensable figure so quickly is a cautionary tale — and perhaps something Prince Harry could learn from.

In many ways, Diana took a leap of faith that day in September 1995 when her brother, Earl Spencer, introduced her to the BBC reporter.

‘He’s quite short,’ she later said. ‘I towered over him.’

Indeed, his lack of stature was later to lead to an unfortunate nickname she coined for him. But that was all in the future.

When the meeting broke up that afternoon, Earl Spencer assumed his sister had seen and heard the last of Bashir. During 90 minutes, according to testimony presented to the inquiry, Bashir made a string of outlandish and outrageous claims about the Royal Family, about courtiers and about Diana’s friends.

Former BBC Director General Lord Hall, pictured, had previously praised Bashir’s journalism

Many were distasteful — Prince Edward having treatment for Aids and, astonishingly, a suggestion that Prince William was unknowingly spying on his mother. Spencer assumed that his sister would see through these preposterous hoaxes but the Princess was hooked. Unknown to her brother, who had apologised profusely to her for having wasted her time, Diana had already made plans to see Bashir again.

Within days, according to his own testimony, they were motoring through southern England together to the New Forest. The trip there and back lasted some five hours, Bashir claimed, and the two talked the entire time.

Later, Diana admitted to me that she had been drawn to Bashir — not in a romantic way, but he was charming.

The fact that he was an unknown figure mattered hugely, she said. ‘He wasn’t a big name and I found that very reassuring.’

The year before, Prince Charles had embarked on his confessional broadcast with Jonathan Dimbleby and ever since, Diana had been considering a television interview of her own.

‘Why shouldn’t I?’ she would frequently ask. This would not be revenge but a reflection of her burning desire for people to hear her voice and her words, unedited. To her, the power of television was hypnotic. She could reach over the heads of advisers, Buckingham Palace and the wider media.

How familiar this all sounds after the revelations of Prince Harry over the past few months.

For Diana, marital separation had not been easy. Frustrated by the intrusions of the paparazzi, she was also damaged by reports about her apparently obsessive relationship with the married art dealer Oliver Hoare — it was claimed she had bombarded Hoare’s wife with silent phone calls — as well as headlines over a friendship with the then newly married England rugby captain Will Carling.

But who could she entrust with such a delicate mission as that interview? Many, many broadcasters beat a path to her door — from America, both Barbara Walters and Oprah Winfrey approached her — while in the UK, dozens of leading journalists and presenters had submitted requests.

In the end, patriotism was critical. She told me she chose the BBC because it was Britain’s national broadcaster, with a reputation for integrity and fair play.

And in Martin Bashir she saw someone whom she thought would let her be herself.

In the past, whenever she had faced criticism, Diana had sought to push the blame onto others. In the row that erupted over her co-operation with Andrew Morton, whose biography of her was an international bestseller, she turned away from those she had actually asked to help him.

One friend, who gave Morton an interview for the book, found calls to Diana went unanswered and he didn’t speak to her for the best part of three years.

But with Bashir it was different.

‘I trusted him,’ she told me when I asked why she had chosen him.

So it was natural that, in the vacuum which developed in her life as staff quit following the Panorama interview, Bashir should fill it. He would help with her speeches and letters, give media advice and draft statements — unpaid, of course, as he was still working for the BBC and basking in the glow of congratulations that had continued to cascade on him in the months after the interview.

The son of a sometime bus driver, Bashir was born in Wandsworth, South London, to parents originally from Pakistan.

One of five children, he converted to Christianity as a teenager and speaks both English and Urdu fluently. An older brother, Tommy, died from muscular dystrophy in 1991 and in the past he has cited his lost sibling as a major influence on his life.

The BBC yesterday announced that all the prizes won by the interview – including this BAFTA – will be handed back

After working as a freelance sports reporter, he moved to the BBC in 1986 and later joined Panorama. Although he had carried out several TV investigations — one involved the financial affairs of then England football manager Terry Venables — he was not first choice to secure a royal exclusive.

But his editors were impressed by his easy, persuasive manner — and Diana herself was utterly convinced. Later on, she invited Bashir and his family to lunch at Kensington Palace — and they didn’t have to travel in the boot.

When doubts about how he had secured the interview began to surface, the Princess more than stuck by him. She sent a handwritten letter that exculpated the reporter from claims he had used forged documents to get to her.

Later, Bashir returned the compliment by relaying a message from the then chief executive of Channel 4, Michael Grade, to tell Diana that ‘he was still a fan’.

All the same, at our lunch, she told me that Bashir had informed her he had ’two contacts at GCHQ’ — the government intelligence organisation — who said she ‘had been bugged by MI5’.

Throughout the mid 1990s, Diana’s concerns about her privacy and security were crucial to her. She believed she was being spied on and that her telephones were routinely bugged. At one stage, she had professionals in to check for listening devices, pulling up priceless palace carpets and lifting floorboards.

Many believe this was at the suggestion of Bashir. And it was through Bashir that Diana became friendly with the troubled ITV presenter Michael Barrymore, whom the two would visit together.

But by the beginning of 1997, her relationship with the reporter was changing. She told me he had signed a book deal with the publisher Random House. It was to be a collection of her speeches, illustrated with photographs of her at the events.

‘Martin says the estimated sales will be £2 million to £3 million worldwide,’ she said.

What was Martin’s cut, I asked? ‘£100,000,’ she replied. ‘He was always complaining about money, that he didn’t get paid enough by the BBC.’ It was clear she was beginning to get cold feet.

Later she told me: ‘Whenever Paul [Burrell] drives him, he pumps him for information, wanting to know who I see, what I do.’

He was especially interested in her men friends. Five in particular: Hasnat Khan, the surgeon she was seeing romantically; Oliver Hoare; businessman Christopher Whalley, who was a friend; the American Gulfstream billionaire Teddy Forstmann; and Professor Sir Magdi Yacoub, the distinguished heart surgeon.

One particular question from the smooth-talking TV man raised yet more suspicions.

‘He wants to know if anything is going to change this year, if I am going to get remarried,’ she said.

By now she was also harbouring doubts about aspects of the Panorama interview. In particular, she bitterly regretted talking about James Hewitt, with whom she admitted that she’d had an affair.

‘I don’t know who to blame for that, Martin or myself,’ she told me. ‘He persuaded me we had to do it because I was vulnerable on men.’

The original aim of the interview, she said, was to also expose the dirty tricks being played on her: phone tapping, her bugged car, etc. ‘It was to be done in two parts,’ she said, ‘but part two never happened.’

Later, she told me that her brother Charles Spencer had warned her not to trust Bashir and she began asking friends for advice.

As the Mail revealed earlier this year, Hasnat Khan was one of the first to warn her to have nothing to do with him.

Prince William put it more bluntly. ‘He said “he’s a sly creep, Mummy”,’ Diana told me.

Soon afterwards, she told Bashir she wanted to back out of the book project, claiming that under the terms of her divorce she could not enter into commercial arrangements. Bashir begged her to write to Prince Charles to ask for his permission to do so but she flatly refused.

Diana now feared that Bashir would exploit their friendship, that she had allowed him to know so much about her life, he could write it all down and turn it into a book. She asked him to promise he would do no such thing. She told me he gave her that undertaking in a fax which she intended to keep.

How did it all end? She stopped taking his telephone calls and changed her mobile number.

And that nickname she bestowed on him? ‘The Poison Dwarf’.