Current Covid vaccines could be reprogrammed to target new strains in just ‘a few days’, experts said today in a bid to calm fears about the South African variant.

Top Government scientists have warned changes to the virus may mean the current wave of vaccines are less effective against it or don’t work at all. Matt Hancock said he was ‘incredibly worried’ about the highly-infectious South African variant, which has already been spotted in two Brits.

But experts told MailOnline today there was no publicly-available data to suggest the strain possesses the ability to escape the current iteration of jabs, even though it is more transmissible.

Professor Ian Jones, a virologist at the University of Reading, claimed he was ‘almost certain’ the vaccines will still be effective at some level.

He added that, in the unlikely event any new strain does makes vaccines redundant, it would take ‘a few days or less’ to tweak the jabs to target them.

Experts are less worried about the Covid strain racing through the UK because it has less changes on its spike protein that would threaten how well vaccines work.

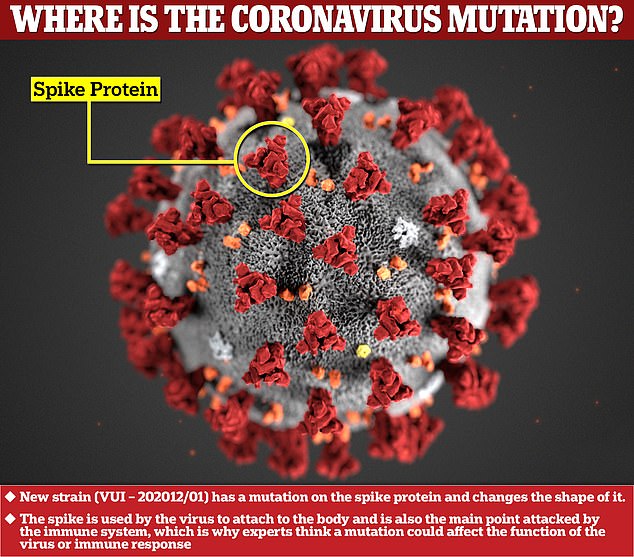

The mutations of the coronavirus has caused changes to the spike protein on its outside (shown in red), which is what the virus uses to attach to the human body (Original illustration of the virus by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

Brian Pinker, 82, became the first person in the world to receive the Oxford University vaccine today

Professor Jones told MailOnline: ‘At the moment there is no data on the ability of either the UK or SA variants to evade the immune response generated by the vaccine.

‘The vaccines all produced multiple antibodies that block the virus-receptor interaction and while the changes in the variants might dodge a few of these they are unlikely to dodge all of them so it is almost certain the vaccine will still be effective at some level.

‘And as long as severe Covid is prevented even a partially effective vaccine would be useful. If a change in the vaccine was required the genetic alternation required could be done in a few days but of course the scale up to millions of doses will take time.’

Vaccine makers have said they are already looking at ways to tweak their jabs to protect people from new variants.

Professor Sarah Gilbert, one of the leading scientists behind the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine, told the BBC today: ‘We are looking at how well [the vaccines] work on these new variants and others that will come in the future.

‘And we’re also thinking about what we’ll need to do if it ever becomes necessary to replace the version of the vaccine we’re using now with a new one.

‘We don’t think we’re at that point yet, there’s no reason to suppose we need to make a switch now but it is possible that in the future we need to make a tweak, a change, to the vaccine.

‘So, with my team, I’m still working on how we make that change really quickly if we ever need to.’

Asked how quickly that change could come if needed, Professor Gilbert added: ‘We don’t expect to have to make a switch in the near future. But we’re thinking that this vaccine is going to be used over a period of many years probably.

‘As with flu vaccines we have a new version every year, which takes into account the changes in flu viruses circulating. Something similar is probably going to have to happen with the coronavirus vaccines.

‘I don’t think it’s necessarily going to be a very rapid switch that we have to make. But what we might be looking at is when we’re coming round to planning vaccinations for next autumn, thinking about another wave at end of 2021, which is a theoretical possibility, we will be considering whether to continue with the same version [of the vaccine] or a different version.’

German firm BioNTech, which helped deliver the Pfizer vaccine approved in the UK last month, said it could use existing technology to produce a new vaccine against mutations of coronavirus in six weeks.

The team’s vaccine uses brand-new mRNA technology, which BioNTech’s chief executive says can be engineered much more easily than traditional vaccines.

The comments came after one of the Government’s coronavirus advisers yesterday claimed there was a ‘big question mark’ over whether any of the current wave of jabs could protect against the mutant strain.

Sir John Bell, regius professor of medicine at Oxford University, argued the South African variant was more concerning than the Kent one because it has ‘pretty substantial changes in the structure of the protein’, meaning vaccines could fail to work.

Covid vaccines — including the Pfizer/BioNTech and Oxford University/AstraZeneca jabs currently being rolled out across Britain — work by training the body to spot the virus’s spike protein.

If the spike mutates so much that it becomes unrecognisable then it could render vaccines useless or make them less potent.

The Covid vaccine protects against the disease by teaching the immune system how to fight off the pathogen.

It creates antibodies – disease-fighting proteins made and stored to fight off invaders in the future by latching onto their spike proteins.

But if they are unable to recognise proteins because they have mutated, it means the body may struggle to attack a virus the second time and lead to a second infection.

However, there is no concrete evidence to suggest the South African strain is more deadly or causes more severe illness than regular Covid.

But South Africa’s health minister, Dr Zweli Mkhize, has warned there has been ‘anecdotal evidence’ of a ‘larger proportion of younger patients with no co-morbidities presenting with critical illness’.

Discussing the threat posed by the South African variant, Mr Hancock told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme today: ‘I’m incredibly worried about the South African variant

‘And that’s why we took the action that we did to restrict all flights from South Africa and movement from South Africa and, in fact, to insist that anybody who’d been to South Africa to isolate.

‘This is a very, very significant problem, in fact I spoke to my South African opposite number over Christmas and one of the reasons they know they have a problem is because, like us, they have an excellent genomic-scientific [programme] to be able to study the details of the virus and it is even more of a problem than the UK new variant.’

It comes after Sir John told Times Radio yesterday: ‘The mutations associated with the South African form are really pretty substantial changes in the structure of the protein.

‘My gut feeling is the vaccine will be still effective against the Kent strain

‘I don’t know about the South African strain – there’s a big question mark about that.’