One in five cancer doctors and nurses in UK hospitals were infected with Covid-19 during the first wave of the pandemic, a study suggests.

The majority of those who had antibodies in their blood – a sign of previous infection – did not recall symptoms of the coronavirus, suggesting their were ‘silent carriers’.

And a substantial proportion — roughly a third — had lost their antibodies within four weeks, which may indicate they at risk of catching the infection again.

The study of 400 oncology staff within the NHS suggests there is a need for more extensive testing of the workforce. Without it, experts said doctors, nurses and radiographers within cancer care, their families and their patients continue to be at great risk of Covid-19.

It comes amid concerns about the provision of treatment for cancer patients during the coronavirus crisis. Up to 50,000 cancer cases have gone undiagnosed over the pandemic, a leading charity warned today.

Millions more have faced delays in crucial treatment because during lockdown the health service focused on Covid-19 patients, while other services, such as cancer care, were scaled back.

Some 33,000 of cancer patients are still waiting now, but with the UK facing a ‘second wave’ of Covid-19, some hospitals have already started restricting services.

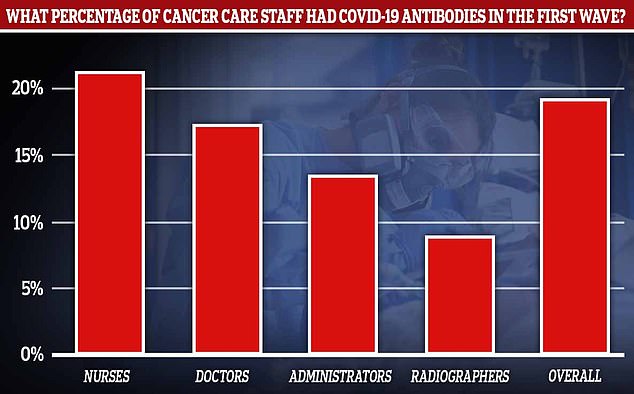

One in five cancer doctors and nurses in UK hospitals were infected with Covid-19 during the first wave of the pandemic, a study suggests. The highest proportion was in nurses

The study included nurses, doctors, radiographers and admin staff in patient-facing roles working at oncology departments at three large East of England NHS Trusts.

These were Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, North West Anglia NHS Foundation Trust and Queen Elizabeth Hospital Kings Lynn NHS Foundation Trust.

At the start of June, staff were given an antigen test, which tells if you are currently infected with the coronavirus.

At the same time they were also given two different antibody tests, which reveal if you have previously had the infection.

No-one tested positive for antigens, meaning they were most likely not infected at the time they were swabbed for the virus.

But 18.4 per cent tested positive for antibodies specific to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, suggesting they had previously been infected.

The highest rates were among oncology nurses (21.3 per cent), followed by doctors (17.4 per cent), administrators (13.6 per cent) and radiographers (8.9 per cent).

Just 38 per cent those who tested positive for the antibodies reported previous symptoms suggestive of Covid-19, suggesting the rest were ‘asymptomatic’ – meaning they did not show symptoms.

However, they may have shown signs of Covid-19 – like a headache or fatigue – but brushed them off as something else.

All staff were retested four weeks later in July to see how their immunity had held up.

Antibodies are parts of the ‘adaptive’ immune system, the part that learns to recognise pathogens so that the next time they enter the body, they can start fighting it off straight away.

Only 13.3 per cent of the staff tested positive for antibodies in July. Of these, 92.5 per cent were previously positive and 7.5 per cent were newly positive.

Of those who tested positive for antibodies in June, 32.5 per cent had become lost their antibodies when retested four weeks later.

The findings indicate that the antibodies waned over time, which means a number of things.

Firstly, it could show that the 18 per cent figure in June was an underestimation of how many staff had actually caught the virus, if those who had it in March of April no longer had antibodies.

And it may mean staff who have had the virus are vulnerable to a second reinfection.

However, even if a test can’t find antibodies circulating in the blood, the body could still rapidly produce them in the future.

It doesn’t necessarily mean the body has forgotten how to fight Covid-19, and a person may have only a milder bout of disease the second time round.

And antibodies are just one of several key components involved in immunity. T cells, types of white blood cells, also play a role in preventing reinfection but can’t be tested for easily.

The truth on immunity is still murky. But the study adds to research this week from Imperial College London that showed 26 per cent fewer Britons have coronavirus antibodies now than at the peak of the first wave.

Imperial College London scientists, who led the research, said they suspect natural protection against Covid-19 lasts between six to 12 months.

Dr David Favara, from Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Cambridge, led the Covid-19 Serology in Oncology Staff (CSOS) Study.

He said: ‘We began work on this research in April 2020, when the UK was still under Covid-19 lockdown.

‘At that time there was no widely available formal testing programme for NHS staff, symptomatic or asymptomatic, and I was concerned about the impact of transmission of the virus to our oncology patients.’

He said he believes this was the first study to specifically investigate exposure to the virus in patient-facing oncology staff who were at work during the peak of the pandemic in the UK between March and June.

‘The UK has guidance from the UK Royal College of Radiologists on testing patients for the virus antigen prior to their radiotherapy treatments, and broad advice for testing staff,’ Dr Favara said.

‘Considering our findings, we propose that there should be a focus on routinely testing oncology nursing staff for both the virus antigen and antibodies until an effective vaccine becomes available.’

A number of top experts have called for regular testing of healthcare workers, whether they have symptoms of not, including Professor Charles Swanton, who works at the Francis Crick Institute and Cancer Research UK’s chief clinician.

The study will be presented next week at the National Cancer Research Institute Virtual Showcase, put on by the UK-based National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI).

At the same briefing, a survey will be presented which suggests 69 per cent of oncology staff believe patients’ access to ‘standard of care treatment’ – meaning the standard NHS treatment available – has been compromised as a result of the pandemic.

Almost 2.5million people missed out on cancer screening, referrals or treatment in the UK at the height of lockdown, according to Cancer Research UK, even though the NHS was never ovewhelmed as feared would happen.

The study also found 66 per cent felt able to do their job without compromising their personal safety.

But 42 per cent of staff felt they were likely to be at risk of poor wellbeing and 34 per cent indicated signs of burnout.

However, the majority said they felt able to work well during this time and an average score of around seven out of 10 was reported, where 10 indicates being able to work to their best.

The survey was of 1,038 doctors, nurses, pharmacists, administrators and allied health professionals working in oncology.